Home > Alcohol Awareness and Prevention in the Age of COVID-19

By Cele Fichter-DeSando, MPM

Alcohol Awareness and Prevention in the Age of COVID-19

Since the 1980’s April has been recognized as National Alcohol Awareness Month. Traditionally, this month has been a time to educate the public about the risks associated with alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (AUD). In 2021, as the world continues to struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic, there is evidence that alcohol consumption has increased for some vulnerable populations. It is more important than ever to take the opportunity to provide resources and support related to alcohol use and AUD.

Alcohol Use Patterns Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

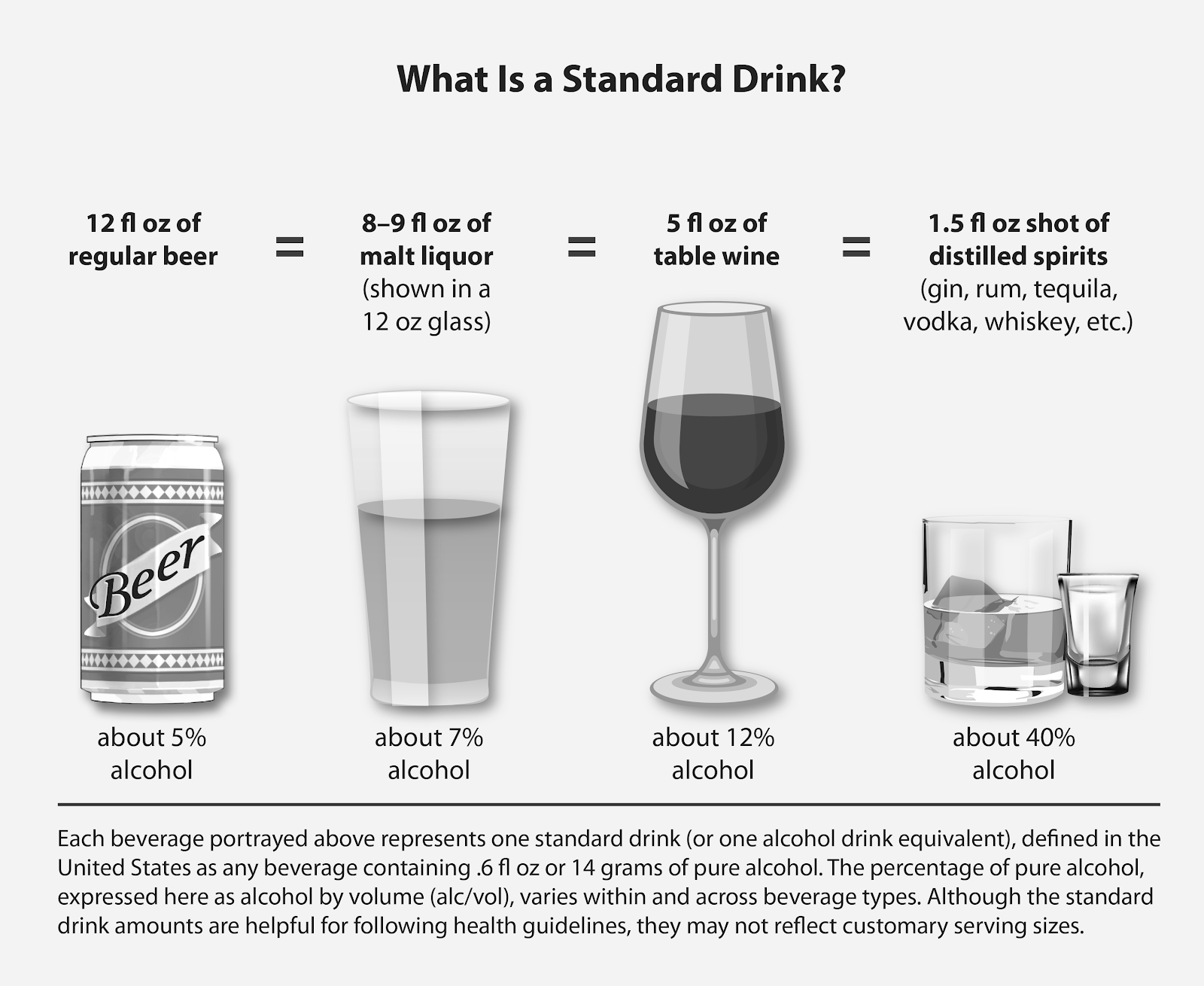

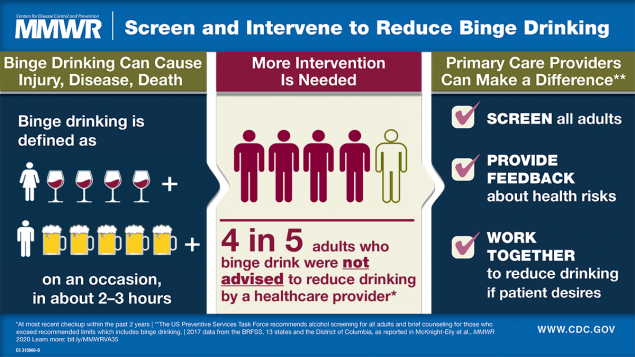

Prior to COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) reported that excessive alcohol use is responsible for about 95,000 deaths a year in the United States. Excessive use includes binge drinking, heavy drinking, and any alcohol use by pregnant women or anyone younger than 21. Binge drinking is defined as consuming 4 or more drinks on an occasion for a woman or 5 or more drinks on an occasion for a man. Heavy drinking is defined as consuming 8 or more drinks per week for a woman or 15 or more drinks per week for a man.1

The 2019 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found that 25.8 percent of people ages 18 and older reported engaging in binge drinking in the past month, and 6.3 percent reported that they engaged in heavy alcohol use in the past month.2

In addition to binge and heavy drinking, researchers have begun to identify a trend among young people known as high intensity or extreme binge drinking.3 High intensity drinking is defined as drinking two or three times the number of drinks associated with the 4-5 + binge drinks per episode. By gender, this is 8-12+ drinks for females and 10-15+ drinks for males in a single occasion. This trend consists of engaging in heavy drinking rituals for holidays, sporting events, vacations, and 21st birthdays celebrations. For some, high intensity drinking decreases with age, but for others the behavior may continue if lifestyle and circumstances stay the same. Marital status, parenthood, full time employment, and other age-related life changes can be associated with a decrease in high intensity drinking. No matter the duration, high intensity drinking is significantly associated with more adverse health and social consequences, like alcohol-related emergency department visits, fights, injuries, driving under the influence, increased sexual behavior, arrests, legal problems, and AUD.4

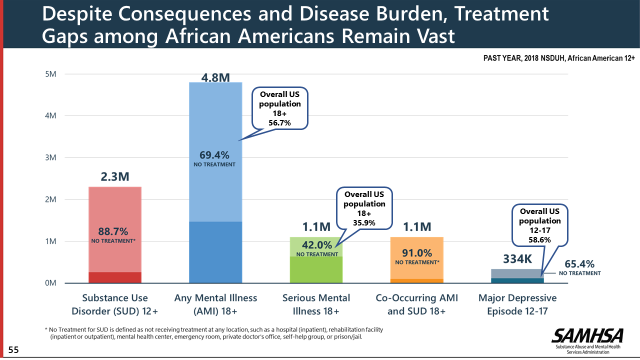

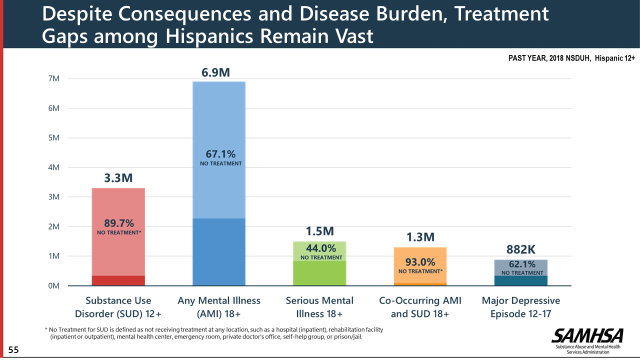

Patterns of binge, heavy, and high intensity drinking can increase an individual’s risk of AUD. According to the 2019 NSDUH, 14.5 million people ages 12 and older had an AUD. An estimated 414,000 of those with AUD were adolescents ages 12 to 17. In 2019 only about 7.2 percent of those 12 and older with AUD received treatment.5 The low rate of those with AUD receiving past year treatment has long been a public health problem. This is especially worrisome during the pandemic when accessing treatment may decrease even further due to lockdowns and restricted access. The rate that different communities access treatment is also of particular concern. The rates of behavioral health disorders for people of color are similar to the general population, but rates in access to treatment among African Americans and Hispanics remain substantially lower6. Improving access to treatment, preventing disruption of treatment, and increasing the capacity for telehealth and recovery support services are of vital importance during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Alcohol Use Patterns and COVID-19

Excessive alcohol use can lead to the development of chronic diseases and other serious problems, including AUD. Binge drinking and heavy drinking can cause heart disease, as well as irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, and stroke.7

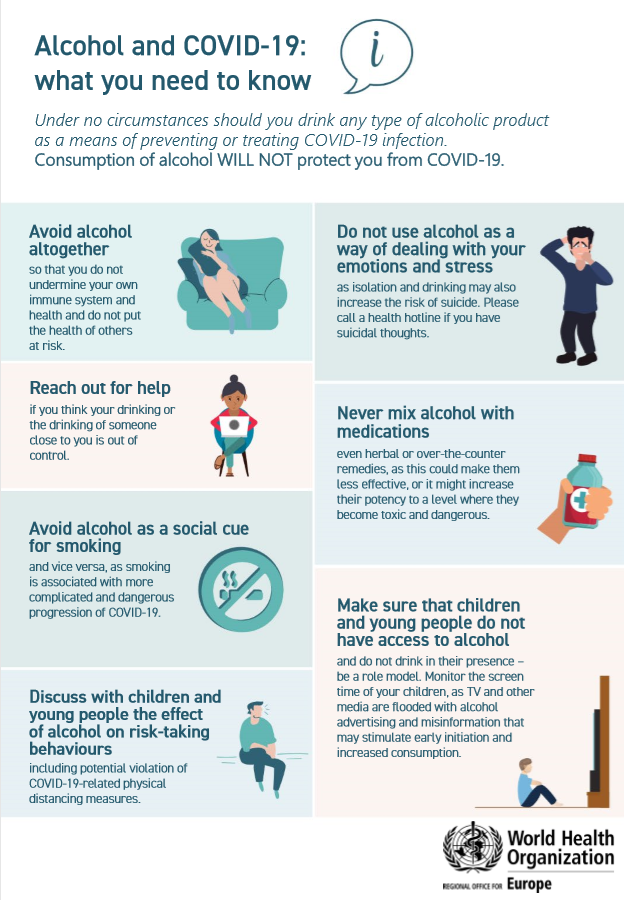

The chronic health conditions associated with AUD and heavy alcohol use are also associated with serious illness if COVID-19 is contracted. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) fact sheet on Alcohol and COVID-19, affects almost every organ of the body and alcohol use, especially heavy use, weakens the immune system and reduces the ability to cope with infectious diseases.8

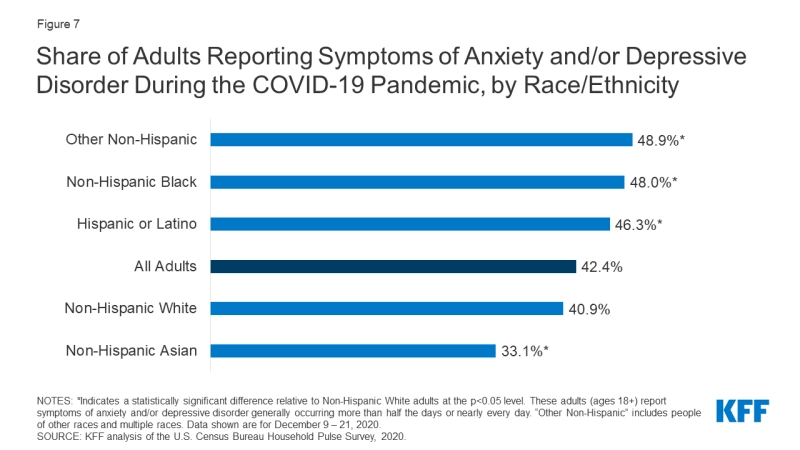

The COVID-19 pandemic, economic recession, and other losses have had numerous negative impacts. The burden of binge and heavy alcohol use was a problem before the pandemic and has affected different groups disproportionately in recent months. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) reports that during the pandemic, about 4 in 10 adults in the U.S. have reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, up from one in ten adults who reported these symptoms from January to June 2019. A KFF Health Tracking Poll from July 2020 also found that many adults are reporting specific negative impacts, such as difficulty sleeping (36%) or eating (32%), increases in alcohol consumption or substance use (12%), and worsening chronic conditions (12%), due to worry and stress over the coronavirus.9 Communities of color are experiencing even greater rates of distress as illustrated in the KFF figure below.

The KFF study and other research show emerging evidence that alcohol consumption has increased for some populations since the pandemic began. A cross-sectional study of 832 adults in the U.S.found that two-thirds of the participants reported increased drinking rates during COVID-19, and that more than one-third (34.1%) reported engaging in binge drinking and seven percent reported engaging in extreme binge drinking. Reasons for the increased consumption included increased stress, increased alcohol availability, and boredom. Those participants who reported being very, or extremely, impacted by COVID-19, consumed more alcohol in the past 30 days than those who did not report being severely impacted.10

Different populations are affected differently by the pandemic and will need different resources and support for their health and well-being. An online survey of 312 college students reported a decrease in alcohol consumption in the number of drinks per week (11.5 to 9.9) and the maximum drinks per day (4.9 to 3.3) for students who moved from living with peers to living with their parents.11 Living with parents may be a protective factor for some students but a survey of 565 LGBTQ university students in the United States found that 32% said they were drinking more since the pandemic began. A survey of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men found about one-third reported that their substance use or binge drinking had increased. Some stress factors cited by the participants included moving home during the pandemic, being isolated from resources and peers, and lack of privacy.12

Individuals with anxiety and depression have been affected greatly during the pandemic. A study by researchers at NYU School Of Global Public Health found that people with anxiety and depression are more likely to report an increase in drinking during the COVID-19 pandemic. 29% of the 5850 online respondents reported increased alcohol use. People with depression were 64% more likely to increase their alcohol use and those with anxiety were 41% more likely to do so. Older adults with anxiety and depression saw a sharper increase in their risk for harmful alcohol use. Adults 40 and over with symptoms of anxiety and depression were about twice as likely to report increased drinking during the pandemic compared to older adults without mental health issues.13

Discussion

Alcohol Awareness and Prevention in the Age of COVID-19 require specific strategies tailored to specific populations and circumstances for maximum impact. Stress, boredom, isolation, job loss, underlying conditions, past experiences, grief, and the severity of an individual’s experience with COVID-19 all affect alcohol consumption. Multiple strategies in multiple environments tailored to meet the needs of specific populations are needed.

Alcohol Awareness and Prevention Strategies

References

13Ariadna Capasso, Abbey M. Jones, Shahmir H. Ali, Joshua Foreman, Yesim Tozan, Ralph J. DiClemente,(2021). Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S., Preventive Medicine, Volume 145, 2021,

1,7CDC. Excessive Alcohol Use. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/alcohol.htm. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

10Grossman, E. R., Benjamin-Neelon, S. E., & Sonnenschein, S. (2020). Alcohol Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey of US Adults. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(24), 9189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249189

3Hingson RW, Zha W, White AM. (2017) Drinking Beyond the Binge Threshold: Predictors, Consequences and Changes in the US. AM J Ped Med. 52 (6) 717-727/

National Consumers League. (2019). Why Nutrition Labeling on Alcoholic Beverages Can Reduce Binge Drinking. 2019. https://nclnet.org/alcohol_binge_drinking/

NIAAA. Rethinking Your Drinking. (2021). https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/Tools/

2NIAA Alcohol Facts and Statistics. (2021). https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

Panchal, Nirmita,Kamal Rabah, Cox, Cynthia and Garfield, Rachel. (2018). The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. 9https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

4Patrick, M. E., & Azar, B. (2018). High-Intensity Drinking. Alcohol research : current reviews, 39(1), 49-55.

Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, Shield KD, Struzzo P, Wojnar M, Gual A. Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Health Care: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Alcohol Alcohol. 2016 Jul;51(4):422-7. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv127. Epub 2015 Nov 15. PMID: 26574600.

12Salerno, J.P., Pease, M., Devadas, J., Nketia, B, & Fish, J.N. (2020). COVID-19-Related Stress Among LGBTQ+ University Students: Results of a U.S. National Survey. University of Maryland Prevention Research Center. https://doi.org/10.13016/zug9-xtmi

SAMHSA. Double Jeopardy: COVID-19 and Behavioral Health Disparities for Black and Latino Communities in the U.S. (Submitted by OBHE) https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/pttc/files/covid19-behavioral-health-disparities-black-latino-communities.pdf6

White HR, Stevens AK, Hayes K, Jackson KM. Changes in Alcohol Consumption Among College Students Due to COVID-19: Effects of Campus Closure and Residential Change. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020 Nov;81(6):725-730. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2020.81.725. PMID: 33308400; PMCID: PMC7754852.

World Health Organization Alcohol and COVID-19 . 2020. 8https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/437608/Alcohol-and-COVID-19-what-you-need-to-know.pdf Retrieved February 27, 2021.

11Helene R. White, Angela K. Stevens, Kerri Hayes, and Kristina M. Jackson Changes in Alcohol Consumption Among College Students Due to COVID-19: Effects of Campus Closure and Residential Change Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2020 81:6, 725-730