By Sarah Davis, MNM

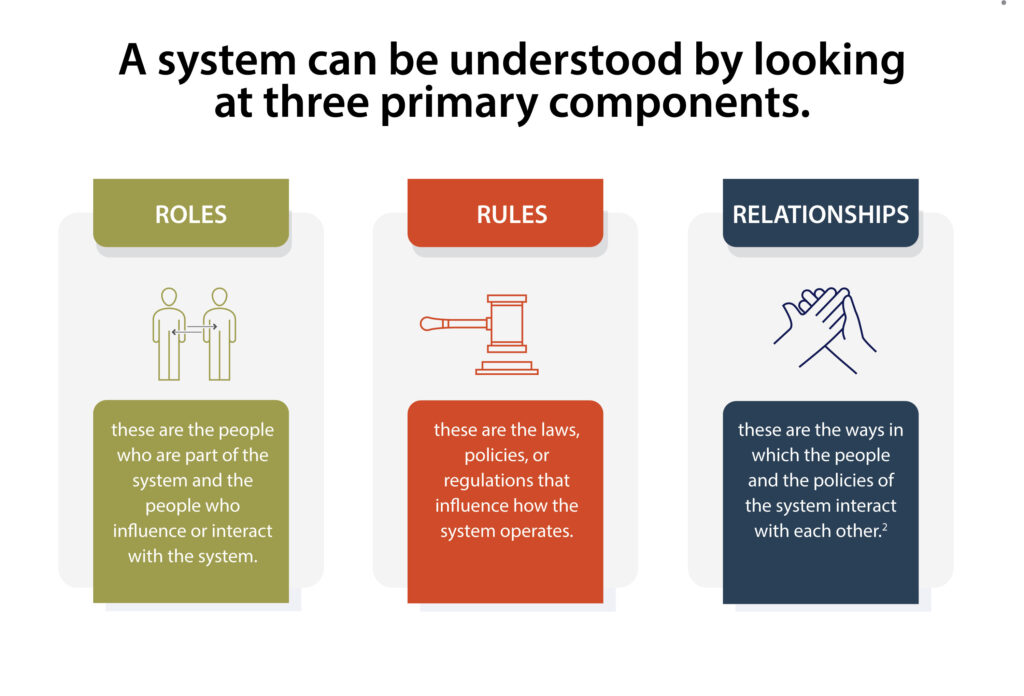

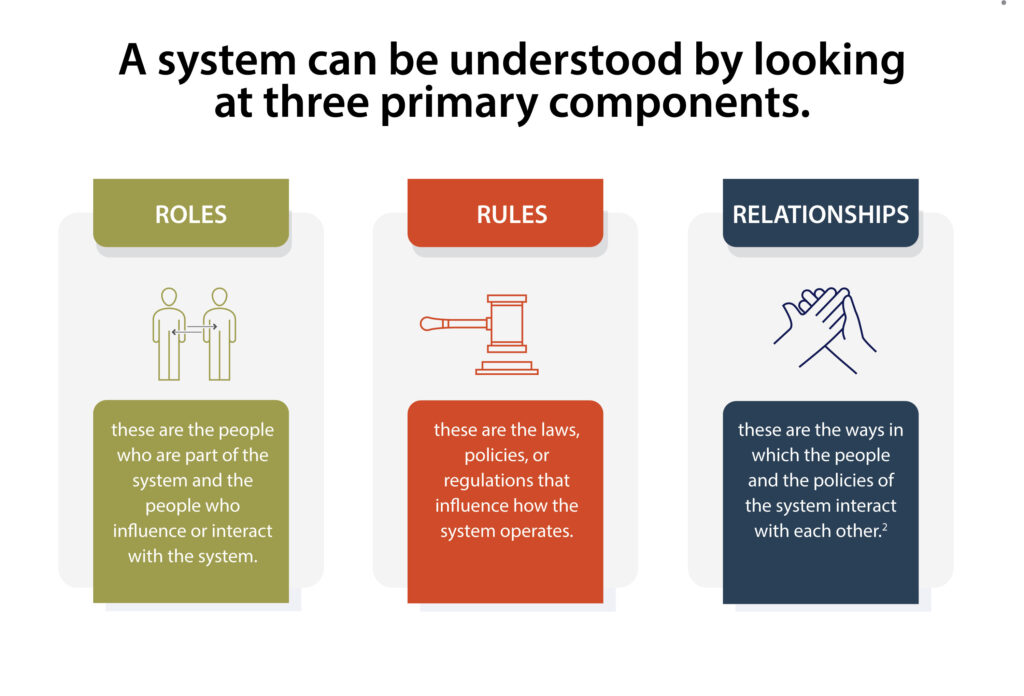

Our world is made up of intersecting and interconnected systems. The work of prevention takes place within the context of these systems (think: education system, healthcare, or judicial system). As prevention professionals work to make changes – at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels1 –it is important to understand how systems work, so that we can influence them to ensure everyone can achieve their greatest level of health and wellbeing.

Schools are an example of a system. A school system could be viewed as a single school, a school district, or the U.S. educational system. Defining the “boundaries” of the system helps you to identify the components within the system, and, most importantly, identify leverage points for change.

In this case, let’s take school districts in our community as the system in question. Within the school district, we identify the following:

Gathering an understanding of the Relationships between the people and the policies within the school district provide prevention professionals the opportunity to see how a system functions (i.e., who has influence over what and how policies impact the system’s functioning). Having a systems perspective enables us to see which parts of a system may be supporting health and wellness, and which parts may be inhibiting it. We can identify and prioritize opportunities for change – and see the people who need to be involved and the policies that need to change.

Systems thinking is the art of seeing and leveraging the connections between components within a system. When prevention professionals build their skills in understanding systems, they expand their opportunities to create lasting and meaningful changes that positively impact health and wellness. For example, if behavioral health in schools has been identified as a need, prevention professionals could ask themselves questions such as:

This is just a sampling of questions, but hopefully give you, a prevention professional, an idea of how taking a systems approach to prevention offers the opportunity to make impactful change based on an understanding of the roles, rules, and relationships that exist within a system.

1 To learn more about the Socio-Ecological Framework for Prevention, check out this planning tool from the Great Lakes PTTC: https://pttcnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Socio-Ecological-Approach-Worksheet_PTTC_Harm-Red._508_kms-FINAL2.pdf

2 This framework of looking at a system is influenced by USAID’s “The 5Rs Framework in the Program Cycle”: https://usaidlearninglab.org/resources/5rs-framework-program-cycle

3 Learn more about Social Emotional Learning from SAMHSA’s Evidence-Based Practices: https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/casel-guide-schoolwide-sel-essentials

By Iris Smith, Ph.D.

Substance use within a family is considered a risk for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). In addition to the association with child abuse or neglect, the death of a parent due to overdose can have significant impact on a young child or adolescent.

A cross-sectional study of the U.S. population estimated that between 1999 and 2020 over one million youth lost a parent to a drug overdose. Most of the parental deaths were among individuals between the ages of 15 and 54. Black, American Indian and Alaskan Native youth are disproportionately affected, with Black youth more likely to experience the death of a father.1

A 7-year prospective study of children who lost a parent to sudden death (suicide, accident, or sudden natural death) found higher rates of psychiatric disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and functional impairment. Depression was more likely in the first two years following the parental death and was more prevalent in youth whose parents died when they were less than 12 years old. Adults who lost a parent during childhood report increased depressive symptoms, diminished self-confidence, educational attainment, and dissatisfaction with interpersonal relationships. This study also found that predeath risk factors, post bereavement child disorder, disruption or loss of social support, and negative life events contributed to severity and duration of impairment.2 Another study of children who experienced parental loss because of opioid-related overdoses between 2002 and 2017 found that within 3 months following the parent’s death, nearly 1 in 10 (11.1%) of the Medicaid-enrolled children had used mental health services. With 5 years this had increased to 1 in 5 (24.8%) and 19.8% had been involved in the child welfare system.3

Families of individuals with substance disorders often face challenges that can affect their physical, emotional, and even financial well being. Children of substance-using parents often grow up in chaotic and sometimes abusive family environments which put them at risk for developing social and emotional problems. Children who reside in marginalized and under-resourced communities are also more likely to be exposed to community level drug-related violence.

At present there are few interventions focused on this growing population of children. Development of evidence-based interventions that address parental loss and bereavement in collaboration with mental health providers are needed to prevent negative developmental outcomes in these children.

Aguirre, L. V. C., Jaramillo, A. K., Saucedo Victoria, T. E., & Botero Carvajal, A. (2024). Mental health consequences of parental death and its prevalence in children: A Systematic Literature Review. Heliyon, 10(2), e24999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24999

Hulsey EG, Li Y, Hacker K, Williams K, Collins K, Dalton E. Potential Emerging Risks Among Children Following Parental Opioid-Related Overdose Death. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):503–504. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0613

Jones CM, Zhang K, Han B, et al. Estimated Number of Children Who Lost a Parent to Drug Overdose in the US From 2011 to 2021. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online May 08, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0810

Kentor, R. A., & Kaplow, J. B. (2020). Supporting Children and Adolescents Following Parental Bereavement: Guidance for Health-Care Professionals. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4(12): pp. 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30184-X

Schlüter B, Alburez-Gutierrez D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Alexander MJ, Kiang MV. Youth (2024). Experiencing Parental Death Due to Drug Poisoning and Firearm Violence in the US, 1999-2020. JAMA. 2024;331(20): pp. 1741–1747. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.839

1 Schlüter B, Alburez-Gutierrez D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Alexander MJ, Kiang MV. Youth Experiencing Parental Death Due to Drug Poisoning and Firearm Violence in the US, 1999-2020. JAMA. 2024;331(20):1741–1747. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.8391

2 Pham, S., Porta, G., Biernesser, C., Walker Payne, M., Iyengar, S., Melhem, N., & Brent, D. A. (2018). The Burden of Bereavement: Early-Onset Depression and Impairment in Youths Bereaved by Sudden Parental Death in a 7-Year Prospective Study. The American journal of psychiatry, 175(9), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17070792

3 Hulsey EG, Li Y, Hacker K, Williams K, Collins K, Dalton E. (2020). Potential Emerging Risks Among Children Following Parental Opioid Related Overdose Death. JAMA Pediatr. 174(5); pp. 503-504.

By Sarah Davis, MNM

Our world is made up of intersecting and interconnected systems. The work of prevention takes place within the context of these systems (think: education system, healthcare, or judicial system). As prevention professionals work to make changes – at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels1 –it is important to understand how systems work, so that we can influence them to ensure everyone can achieve their greatest level of health and wellbeing.

Schools are an example of a system. A school system could be viewed as a single school, a school district, or the U.S. educational system. Defining the “boundaries” of the system helps you to identify the components within the system, and, most importantly, identify leverage points for change.

In this case, let’s take school districts in our community as the system in question. Within the school district, we identify the following:

Gathering an understanding of the Relationships between the people and the policies within the school district provide prevention professionals the opportunity to see how a system functions (i.e., who has influence over what and how policies impact the system’s functioning). Having a systems perspective enables us to see which parts of a system may be supporting health and wellness, and which parts may be inhibiting it. We can identify and prioritize opportunities for change – and see the people who need to be involved and the policies that need to change.

Systems thinking is the art of seeing and leveraging the connections between components within a system. When prevention professionals build their skills in understanding systems, they expand their opportunities to create lasting and meaningful changes that positively impact health and wellness. For example, if behavioral health in schools has been identified as a need, prevention professionals could ask themselves questions such as:

This is just a sampling of questions, but hopefully give you, a prevention professional, an idea of how taking a systems approach to prevention offers the opportunity to make impactful change based on an understanding of the roles, rules, and relationships that exist within a system.

1 To learn more about the Socio-Ecological Framework for Prevention, check out this planning tool from the Great Lakes PTTC: https://pttcnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Socio-Ecological-Approach-Worksheet_PTTC_Harm-Red._508_kms-FINAL2.pdf

2 This framework of looking at a system is influenced by USAID’s “The 5Rs Framework in the Program Cycle”: https://usaidlearninglab.org/resources/5rs-framework-program-cycle

3 Learn more about Social Emotional Learning from SAMHSA’s Evidence-Based Practices: https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/casel-guide-schoolwide-sel-essentials