Home > PTTC Post Article - November 2020

Teresa Brewington MBA, M.Ed, of Coharie and Lumbee tribes, was interviewed for our November feature article. Teresa is the Program Manager of K-12 School Mental Health Supplement funding at the National American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Technology Transfer Center (MHTTC), based in the Native Center for Behavioral Health at the University of Iowa College of Public Health. Author: Van Wilson, Program Coordinator at the PTTC Network Coordinating Office.

As a kid growing up in North Carolina, basketball was life for Teresa.i Her skill as a starting guard was undeniable, having sharpened her abilities in countless hours playing with her dad. In high school, her parents divorced and she moved with her mom and older sister to Raleigh. Her Coharie and Lumbee identity felt far away in this non-native town. She excelled in her first year on the high-school junior varsity team – but was shattered as she watched benchwarmers move to varsity after the coach told her he didn't want ‘her kind’ on the team.

Like nearly all teens in their formative years, Teresa internalized many of the messages she received about herself and her identity.ii This message was direct and damaging to her self-worth and Native identity. Soon after, Teresa started drinking and dropped out of high school.

The Lumbee and Coharie have a rich history of protecting and owning their education.iii In 1885, with the help of their state representative Hamilton McMillan, the Lumbee and Coharie tribes were provided separate schools, their own school committees, and the right to select their own teachers.iv By 1924, Robeson County Indian schools had a total enrollment of 3,400 students. Both of Teresa’s parents attended Native American schools and were taught by Native American teachers. In 1887 the Croatan Normal School, now known as the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, was established to train Native American public school teachers - it remained the only state-supported, four-year college for Native Americans in the nation until 1953.v

Two years after Teresa dropped out of high-school, with the encouragement of her sister, Ranessa Brewington, and the force of Lumbee and Coharie history and values on her side, Teresa returned to her roots and enrolled in University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Here, she learned about the values and theory of Social Justice and graduated with degrees in both Sociology and Juvenile Justice. She has since worked professionally in juvenile justice, mental health counseling, foster care, education and administration settings - all with an emphasis on serving her Native communities. Teresa is currently Program Manager of K-12 School Mental Health Supplement funding at the National American Indian and Alaska Native (NAIAN) Mental Health Technology Transfer Center (MHTTC), based in the Native Center for Behavioral Health at the University of Iowa College of Public Health, which also operates the NAIAN Addition Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) and the NAIAN Prevention Technology Transfer Center (PTTC).

Teresa reflects on the experience with her basketball coach as an adult, “Words can hurt people. As teachers and parents, and people that children look up to, your words matter. You can destroy a child, or you can make a child.” A self-described ‘protector’, Teresa is the embodiment of prevention ‘protective factors’. She harnessed the resilient Native American spirit and vowed to instill her sense of beauty and worth in the lives of the Native American children with whom she worked.

“When I’m given the opportunity, I put positive words in a child’s voice because they may not hear it otherwise. Even a few small words may touch and change a child’s life - just a few words changed mine.” Teresa continues, “Native American people are beautiful people. We are unique and wonderful. We are business owners. We are college educated, Ph.D. graduates, and professors. We pay taxes and own land and homes. We are artists, poets, writers, dancers, and drummers. We are seamstresses, jewelry makers, and craftsmen. We love our children and take care of our elders.”

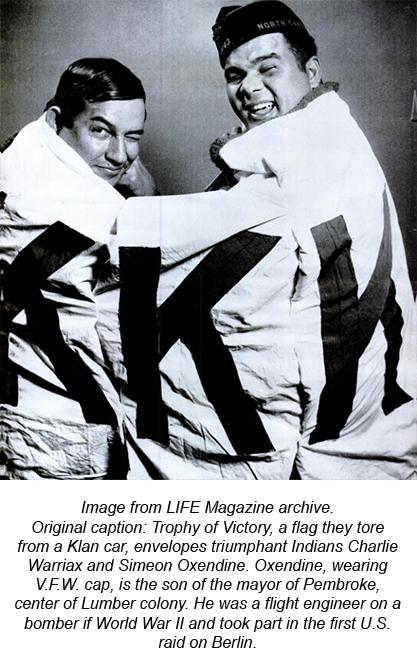

This assertion of Native American worth and celebration of Native American peoples and cultures is at the core of Native American Heritage Month, observed over the month of November.vi Teresa shares a celebrated event from 1958 which galvanized the Lumbee community and spread internationally when it was covered by LIFE magazine.vii It has since been well researched, documented, and memorialized on the site of the encounter.viii The Lumbee endured years of harassment from the Klu Klux Klan, which had risen again in North Carolina following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme court ruling. The local KKK leader planned a rally for the night of January 18, 1958, to, in the leader’s words, “put the Indians in their place, [and] end race mixing.” About a hundred Klansmen, with a large KKK banner, gathered in a field around a small speaker and single light bulb powered by a generator. Differing accounts claim at least 350 and at most 1000 Lumbee surrounded the Klansmen in the darkness. A Lumbee sharpshooter took out the lone lightbulb, and a shuffle ensued with gunshots ringing into the air, sending the outnumbered Klansman fleeing. There were only a couple minor buckshot injuries, and one arrest - a Klansman charged with drunkenness and carrying a concealed weapon.

This assertion of Native American worth and celebration of Native American peoples and cultures is at the core of Native American Heritage Month, observed over the month of November.vi Teresa shares a celebrated event from 1958 which galvanized the Lumbee community and spread internationally when it was covered by LIFE magazine.vii It has since been well researched, documented, and memorialized on the site of the encounter.viii The Lumbee endured years of harassment from the Klu Klux Klan, which had risen again in North Carolina following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme court ruling. The local KKK leader planned a rally for the night of January 18, 1958, to, in the leader’s words, “put the Indians in their place, [and] end race mixing.” About a hundred Klansmen, with a large KKK banner, gathered in a field around a small speaker and single light bulb powered by a generator. Differing accounts claim at least 350 and at most 1000 Lumbee surrounded the Klansmen in the darkness. A Lumbee sharpshooter took out the lone lightbulb, and a shuffle ensued with gunshots ringing into the air, sending the outnumbered Klansman fleeing. There were only a couple minor buckshot injuries, and one arrest - a Klansman charged with drunkenness and carrying a concealed weapon.

These personal and communal stories of overcoming seemingly endless persecution are woven deeply into the sordid history of U.S. colonization, yet not widely taught in U.S. educational settings. Many Native Americans are pleased that November has been designated as Native American Heritage month, but believe it is widely overshadowed by the Thanksgiving Holiday, which is typically surrounded by inaccurate and whitewashed versions of history which omit the atrocities experienced by Native peoples.x

Teresa asserts “Native American Heritage Month is needed now as a reminder to everyone what Native Americans have contributed to what is now the United States. Even in the beginning Native Americans have done a lot for our country and communities. Farming, fur trapping, and canoes came from Native Americans. There is so much we have provided to our country over the years. People have to look past stereotypes and color, and see the individual for who they are - how you impact the world, how you see the world, and how you treat the world and others.” Within the Native American community, Teresa shares “it is a time for celebrating our culture, sovereignty, and identity - and being with your family and friends, and pow-wows – when it is safe as COVID-19 subsides.”

Teresa reflects on a dynamic she observes frequently, “Many people, when they look at Native Americans, it's very easy to look at the negativity because there are so many obstacles facing Native communities today. This is the one month where we are all encouraged to celebrate Native American accomplishments, instead of dwelling on the remaining obstacles.” In this same spirit, our readers are encouraged to make an intentional effort to acknowledge and celebrate the contributions of Native Americans and the inherent worth and value of Native lives. Seek out accurate history and ways to connect with and support Native Communities in your area. Lastly, seek to be the protective force that Teresa so resiliently embodies, and strive to “...put positive words in a child’s voice”.

i. Information collected from interview with Teresa Brewington, October 2020. Conducted by staff from the PTTC Network Coordinating Office, Van Wilson, MSW, MPH, Viannella Halsall, MPH, CHES, Holly Hagle, PhD.

ii. Michal (Michelle) Mann, Clemens M. H. Hosman, Herman P. Schaalma, Nanne K. de Vries, Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion, Health Education Research, Volume 19, Issue 4, August 2004, Pages 357–372, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg041

iii. From ENCYCLOPEDIA OF NORTH CAROLINA edited by William S. Powell. Copyright © 2006 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org. https://www.ncpedia.org/lumbee/rights

iv. From ENCYCLOPEDIA OF NORTH CAROLINA edited by William S. Powell. Copyright © 2006 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org. https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/mcmillan-hamilton

v. From ENCYCLOPEDIA OF NORTH CAROLINA edited by William S. Powell. Copyright © 2006 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org. https://www.ncpedia.org/university-north-carolina-pembroke

vi. https://nativeamericanheritagemonth.gov/

vii. Bad Medicine for the Klan, North Carolina Indians break up Klu Kluxers' anti-Indian meeting. (1958, January 27). LIFE, 26-28

viii. Peng, I. (2019, October). The Day the Native Americans Drove the KKK Out of Town. Narratively. Retrieved from https://narratively.com/the-day-the-native-americans-drove-the-kkk-out-of-town/

ix. From ENCYCLOPEDIA OF NORTH CAROLINA edited by William S. Powell. Copyright © 2006 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org. https://www.ncpedia.org/history/20th-Century/lumbee-face-klan

x. https://www.powwows.com/a-more-accurate-view-of-thanksgiving/

My name is Teresa Brewington, and I am the Manager for the National American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health TTC – K- 12 School Supplement at the University of Iowa, located in Iowa City, Iowa.

I am a Native American woman; I belong to the Coharie and Lumbee Tribes in North Carolina. My Lumbee origin comes from my mother; my father is Coharie. Both tribal communities are linked to the Croatan Indian Tribe from the late 1500’s. Our tribal language is Siouan; although very few elders still exist that speak this fluently.

I received my undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, a school that is historically the first Native American owned school. In college, I studied Criminal Justice because, initially, I wanted to go into law. My junior year changed my life because it put me on another path, an area that I am still passionate about. I took a class called Introduction to Social Work as an elective. This course opened my eyes to learning about people, humanity, racial issues, inequalities, social classes and our society. Afterward, I was inspired to help others, and I graduated with a major in Criminal Justice and Sociology, which later evolved into a degree in School Social Work. I have a Master’s in Educational Leadership, a Master’s in Business Administration, and am working towards a Master’s in Counseling and my Ph.D. in Educational Leadership from Northcentral University.

In addition to my educational experience, I’ve held positions as a director at several mental health agencies. I also served as a supervisor for a foster care agency, where I worked directly with the Salt River Pima Indian Community placing Native American children in foster homes. I have also been a School Guidance Counselor where most of the students were Hispanic/Latino, and an Elementary School Principal for native children at Meskwaki Settlement, located in Iowa, where I currently reside. I want to break down the barriers that exist and bring positive changes for my Native American brothers and sisters.