Home > PTTC Post Article - February 2022

By Cele Fichter-DeSando, MPM

"In the depths of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer."

- Albert Camus

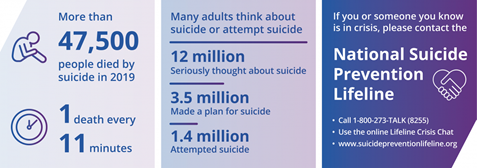

Suicide is a highly complex, preventable public health problem. Globally, more than 700,000 people die each year due to suicide. Suicide is the 4th leading cause of death throughout the world among 15-19-year-olds.

In the United States, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death, with prevalence estimates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors varying by sociodemographic factors, region, and state requiring targeted evidenced-based strategies and interventions.

The Role of Prevention

Suicide is a serious public health problem with tragically painful consequences for individuals, families, communities, the nation, and the world as a whole. When facing a health crisis of such magnitude, it is difficult to know where to begin and how to proceed. Prevention practitioners with their knowledge and experience of protective and risk factor theory can bring hope and strategic action to develop effective suicide prevention programs. As with other evidence-based prevention programs, there is not a single approach or strategy to address suicide prevention. A comprehensive, multifaceted, data-driven plan is essential.

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed LIVE LIFE: An implementation guide for suicide prevention in countries. The guide recommends that effective prevention programs are not built on a single approach but utilize a foundation of six pillars:

The six pillars are the infrastructure that supports four interventions and should be part of a comprehensive suicide prevention strategy.

Prevalence Data to Guide Prevention Programs and Reduce Disparities

To accurately assess, identify, plan, and evaluate suicide prevention programs, there needs to be an understanding of the risk factors and patterns of suicide and suicidal behavior. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently released a surveillance summary report summarizing 2015–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data collected from 254,767 respondents regarding national-, regional-, and state-level prevalence of suicidal thoughts, planning, and attempts by age group, sex, race and ethnicity, region, state, education, marital status, poverty level, and health insurance status. This surveillance data and accompanying tables can be used to design local, regional, and state programs that increase protective factors and decrease risk factors.

Risk Factors

Surveillance and prevalence data along with an understanding of specific risk and protective factors can serve as a roadmap for designing comprehensive suicide prevention programs. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline outlines risk factors that make it more likely that someone will consider, attempt, or die by suicide. Programs and strategies that are designed to reduce risk factors are an important component of suicide prevention. Specific Risk factors for Suicide include:

Protective Factors

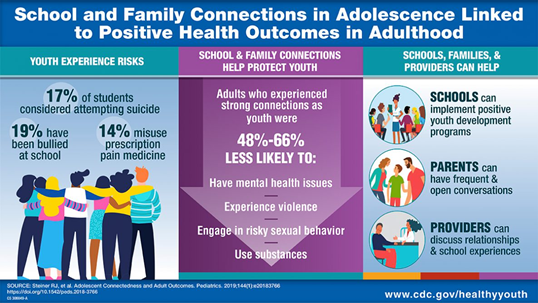

CDC promotes increasing connectedness as a key protective factor strategy for suicide prevention. Connectedness is defined as the degree to which a person or group is socially close, interrelated, or shares resources with other groups or persons.

Substance use prevention programs are provided in multiple settings across multiple timeframes and can increase opportunities for connectedness. Connectedness and social support strategies can be tailored to provide outreach to particular groups identified by The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as groups who may be at risk for suicide. These groups include: youth and young adults, LGBTQ+, American Indians, Alaskan Natives, middle-aged men, veterans, older adults, attempt survivors, disaster survivors, loss survivors and other groups who may be at risk. CDC outlines protective factors that individuals and communities can promote to increase protection from suicidal thoughts and behaviors:

Science into Practice: Call to Action

Prevention practitioners are adept at creating collaborations and utilizing and disseminating resources to put science into practice. Each year as prevention programs conduct needs assessment, set goals and design action plans for their communities, suicide prevention should be included as an integral part of the overall prevention plan. Science and data driven resources are available for prevention practitioners to utilize in developing and participating in effective suicide prevention programs.

Action Alliance tells us that we all play a role in developing and delivering effective suicide prevention. Substance misuse prevention practitioners plan, implement and evaluate effective, data-driven programs and practices that reduce behavioral health disparities and improve wellness. They are critical to suicide prevention efforts. Prevention practitioners bring invincible summer to the depths of winter.

Author's Note

Cele Fichter-DeSando, MPM (She, Her) is a consultant and trainer in substance use and gambling prevention and tobacco prevention and control. Cele has a Master’s degree in Public Management from Carnegie Mellon University and more than 35 years of experience in the management, training, and implementation of research-based prevention programs in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. In 2020, Cele started a certified woman-owned business, CFD Consulting LLC, and has provided consulting for numerous organizations including Tobacco-Free Allegheny, the PTTC Network, and the Danya Institute Central East ATTC. She is passionate about providing resources, materials, and practical applications for evidenced-based prevention programs and prevention science to prevention practitioners.

Cele Fichter-DeSando, MPM

CFD Consulting, LLC

[email protected]

412-580-3089

References

Costanza, A., Amerio, A., Odone, A., Baertschi, M., Richard-Lepouriel, H., Weber, K., Di Marco, S., Prelati, M., Aguglia, A., Escelsior, A., Serafini, G., Amore, M., Pompili, M., & Canuto, A. (2020). Suicide prevention from a public health perspective. What makes life meaningful? The opinion of some suicidal patients. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis, 91(3-S), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i3-S.9417

Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Hoenig JM, Gyawali S, Park-Lee E, Hedden SL. Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years — United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71(No. SS-1):1–19. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7101a1

King CA, Brent D, Grupp-Phelan J, et al. Prospective Development and Validation of the Computerized Adaptive Screen for Suicidal Youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):540–549. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4576

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/article-abstract/2775993

Scarth, B., Bering, J. M., Marsh, I., Santiago-Irizarry, V., & Andriessen, K. (2021). Strategies to Stay Alive: Adaptive Toolboxes for Living Well with Suicidal Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8013. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158013

Stone, D.M., Holland, K.M., Bartholow, B., Crosby, A.E., Davis, S., and Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policies, Programs, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2022.

https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/suicide-prevention

World Health Organization (WHO). 2022 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/ss/ss7101a1.htm?s_cid=ss7101a1_w

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) 2022.