Home > PTTC Post Article - August 2019

Zili Sloboda, Sc.D.

President, Applied Prevention Science International

As prevention practitioners working in the 21st century, we have many prevention tools that were developed over the past 40 years to assess the vulnerabilities of populations to substance use. For that, we need to credit the epidemiologic research in the 1970s, which paved the way for understanding the determinants of the initiation of substance use and progression to deeper involvement with substances. This research included longitudinal survey studies that followed cohorts of children and adolescents into adulthood (e.g. Brook, Brook, De La Rosa et al, 1998; Chen and Kandel, 1995) as well as secondary analysis of data from mainly household and student surveys conducted periodically (http://monitoringthefuture.org/; www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health). We could then see how long people used substances, what happened with long-term use, and what happened when they stopped—all possible from this extensive research that continues today (Sloboda, 2005), MTF, NSDUH].

David Hawkins and his colleagues at the University of Washington reviewed and summarized this research in a 1992 key article that outlined what was then termed the risk factors associated with the initiation of substance use (Hawkins et al, 1992). In the same year, the National Institute on Drug Abuse published a monograph summarizing the factors associated with the progression from initiation to abuse (Glantz & Pickens, 1992). These two seminal works formed the basis to assess individual and population risks through screening tools and population surveys that would enable the provision of the most appropriate prevention interventions.

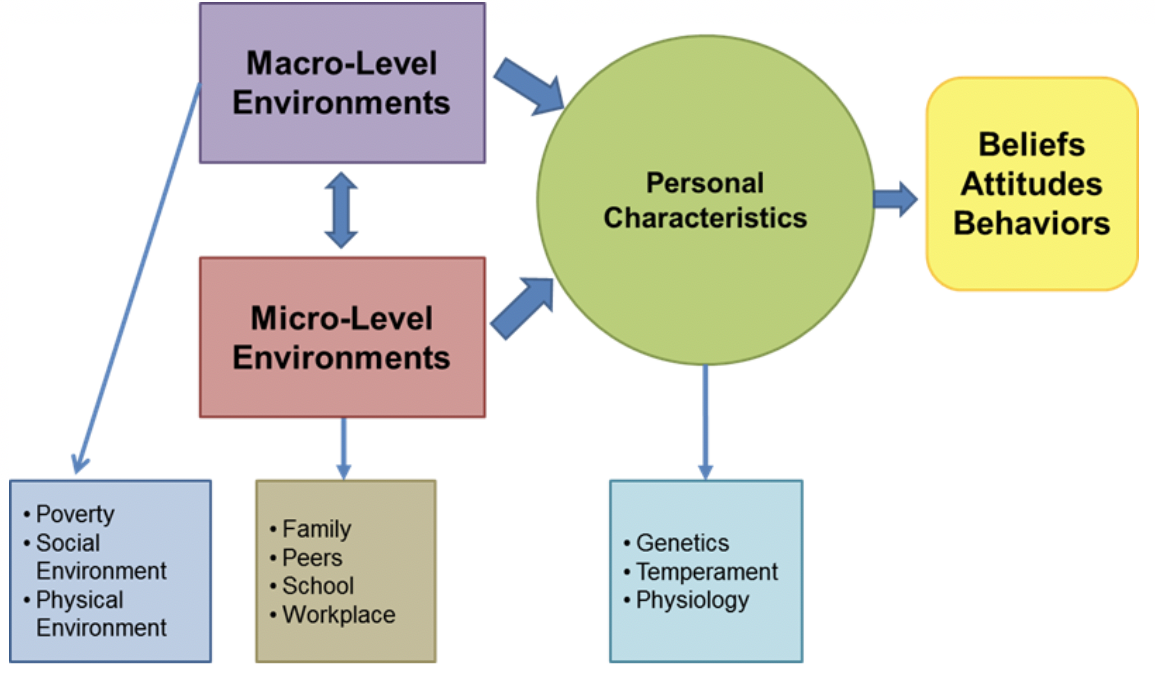

Research on the genetic, physical, and environmental bases and their interactions to establish vulnerabilities for substance use and other such behaviors has led to a reconceptualization of risk and protective factors that has the potential to refine prevention delivery and implementation systems (Sloboda et al., 2012). A simple version of these interactions is seen in Figure 1.

Research on the genetic, physical, and environmental bases and their interactions to establish vulnerabilities for substance use and other such behaviors has led to a reconceptualization of risk and protective factors that has the potential to refine prevention delivery and implementation systems (Sloboda et al., 2012). A simple version of these interactions is seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 helps to elucidate the concept of vulnerability and provides a further understanding of risk and protection as the interface of the physical, psychological, genetic individual and the many environments that influence human development — parents and family, school, faith-based organizations, peers, workplace and close and distant communities.

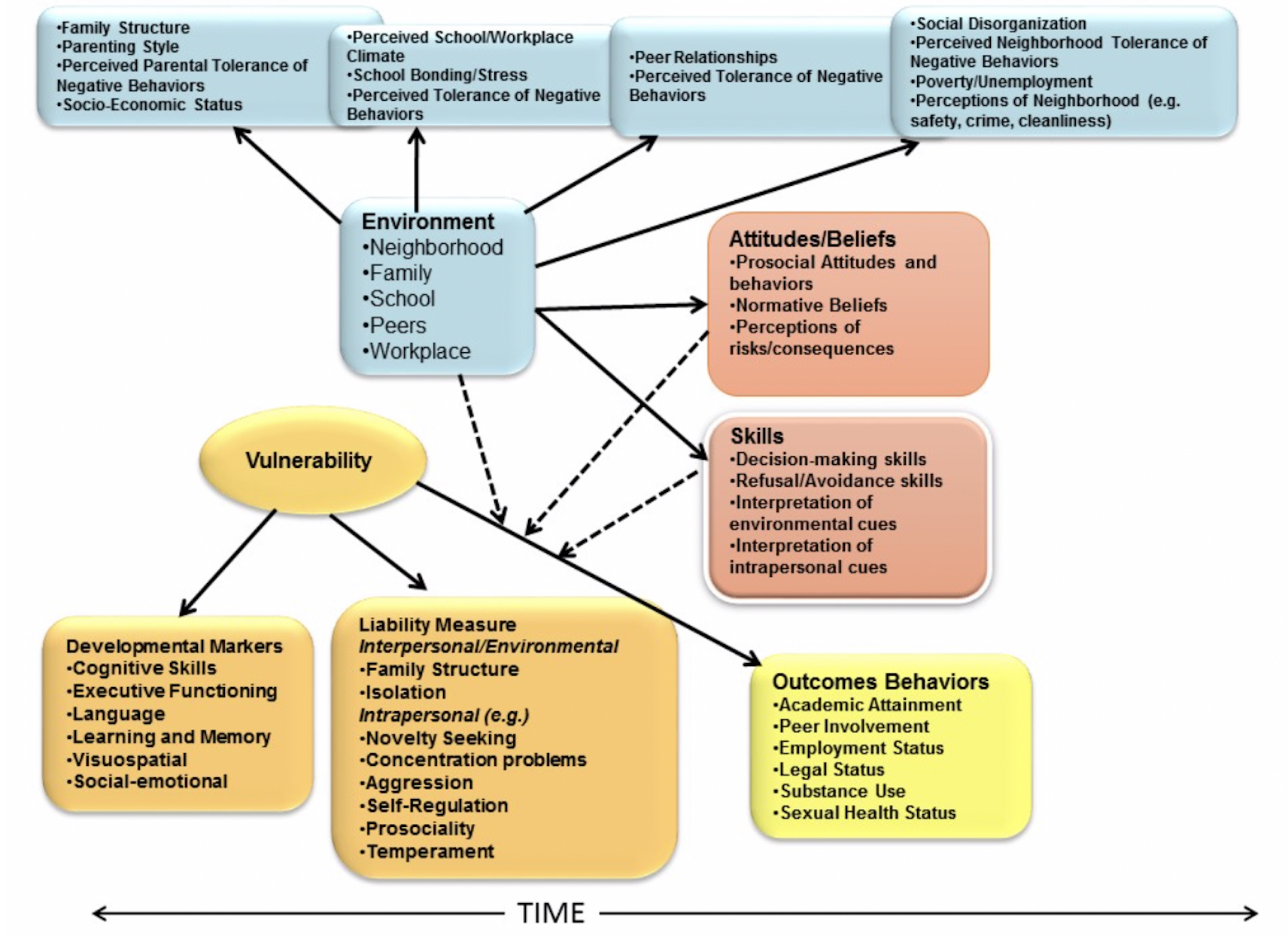

Below is a more complex figure that tries to capture most of the potential macro- and micro-level interactions with the individual and his/her developmental, personality, and other differences that make a person more or less vulnerable to substance use and other negative behaviors.

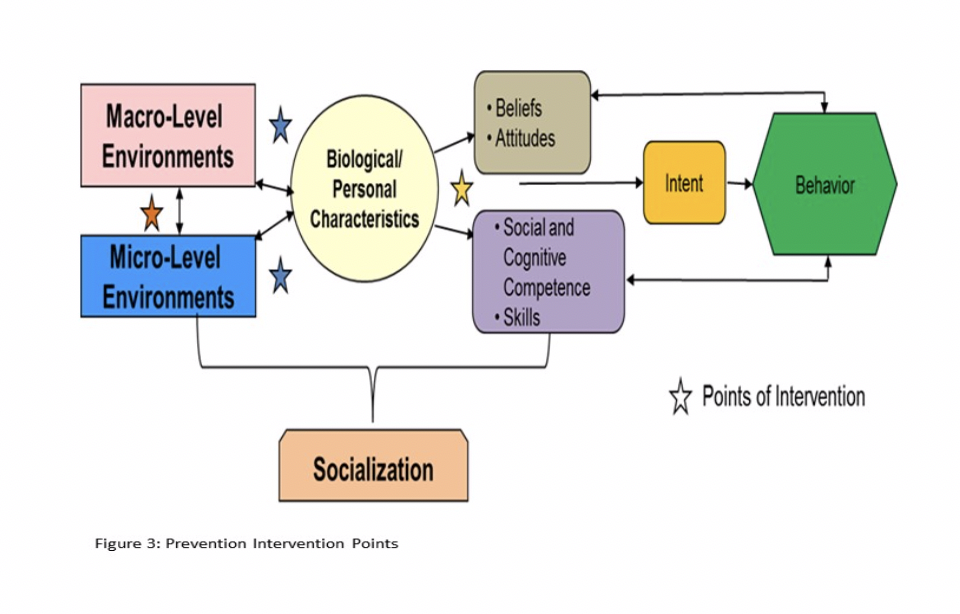

This framework illustrates the factors involved in human motivation and change processes we work with in prevention. It shows how the various environmental levels and personal characteristics interact in the decision-making that takes place before the substance use and performance of other problem behaviors. This interaction is called socialization. Socialization is the process involved in learning the culture, attitudes, beliefs, language, and behavior of the society within which we live. The key term here in socialization is learning. Evidence-based prevention teaches the acceptable attitudes and behaviors of society in order to avoid substance use and become successful, healthy adults.

As mentioned earlier, genetics and other biological factors play a significant role in the achievement of developmental benchmarks, that is, the goal of each stage of development, from infancy to early adulthood, includes: intellectual ability, language development, cognitive, emotional, and psychological functioning, and attainment of social competency skills.

The extent to which developmental benchmarks are met determines our level of vulnerability to influences from our environment. Such vulnerability can vary within an individual and across developmental periods. Children who don’t reach early developmental benchmarks are most likely the most vulnerable as failure to achieve these early benchmarks signifies their difficulties in reaching later ones.

Environmental factors can both lessen or enhance this vulnerability. As environmental experiences are associated with heightened stress or adversity, the risk for substance use is increased. The environmental influences are viewed at two major levels, those in close proximity to the individual—micro level environments—and those that are more distant—macro level environments.

It is the combination of these environmental influences and personal characteristics of individuals that shapes beliefs, attitudes, and behavior. So it is possible for vulnerable children who receive positive parenting to overcome their challenges while similarly vulnerable children who are neglected by their parents may not be so successful (Hill et al., 2010).

What is also important to note is that the two levels of influence--the macro- and micro-level--do not operate independently to influence our behavior, but they also impact one another. For instance, family stability and even parenting behaviors can be challenged when one or both caregivers are unemployed for long periods of time (Dom, Samachowiec, Evans-Lacko et al., 2016; Henkel, 2011; Moustgaard, Avendano, & Marikainen, 2018; University of Oxford, 2017). Children living in impoverished or disorganized neighborhoods, may be at risk or not feel safe (Henkel & Zemlin, 2016).

It is the interface where the micro- and macro-level environments interact with the individual that shapes cognitive and emotional development as well as beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that serve to socialize human beings to become productive members of their communities. These interfacial connections also provide opportunities for interventions to improve or enhance positive growth. The interfaces can either be positive or negative---translated into risk or protection.

Examples of these processes come from our own experiences. Think about a child living in poverty with parents who are absent—either through incarceration, addiction, or even working two or three jobs. Now think about this child but now she has a grandparent or other caring, supportive adult who can help her meet her developmental benchmarks. Or think about this child entering school where she feels safe and accepted. She is more likely to develop prosocial attitudes and engage in prosocial and healthy behaviors because of this bonding or attachment process. Feelings of ‘belonging’ and being supported are key to human development. Now let us think about this girl without a safe and supportive family member or school environment. What if there is a street gang that makes her feel a sense of belonging? What if this gang traffics drugs or engages in criminal behavior?

These are not hypothetical situations, they are often reality. Evidence-based prevention interventions are designed to help parents and families in stress to focus on positive parenting to help their children. They are designed to help schools create safe and positive environments where not only children are happy but also the school staff. Similarly workplaces should be seen as safe and supportive environments for workers.

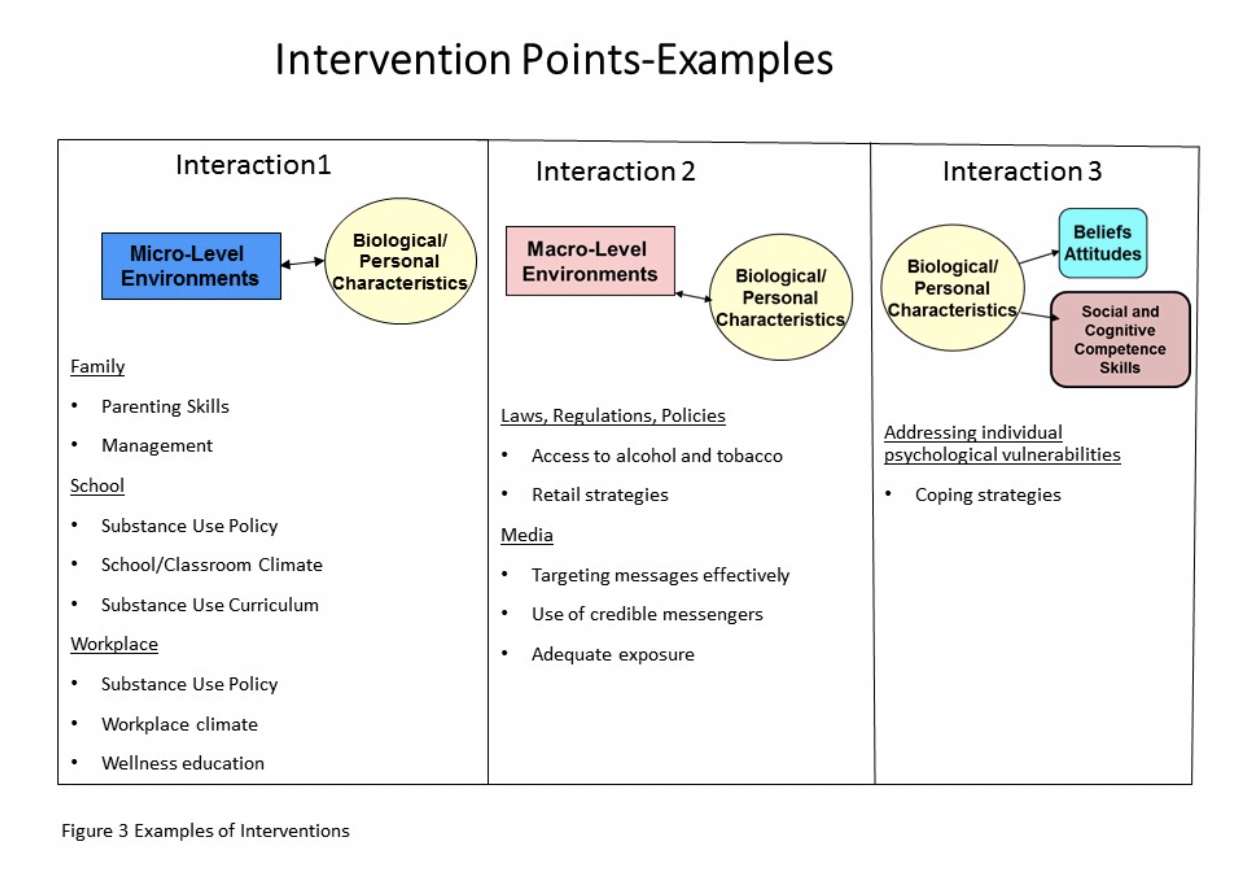

The Vulnerability Model (Figure 1) also serves to guide the development of prevention approaches (Figure 3 below) through a process called socialization. The socialization process involves learning the culture, attitudes, beliefs, language, and behavior of the society within which we live. The process of prevention helps key socialization agents (e.g., parents and other family members, teachers, laws and regulations) to improve their socialization skills such as improving parenting or teaching skills or modifying the setting to make it more difficult to engage in negative behaviors, e.g., requesting proof of age to prevent underage youth from accessing alcohol or tobacco. Thus, the family, school, and community environment become positive forces in raising children to resist engaging in substance use or other risky behaviors.

What this also means is that these prevention interventions are designed to help prevention specialists become socialization agents themselves by directly engaging with the target groups in the socialization process; or they train key socialization agents, such as, parents and teachers to improve their socialization skills, e.g., parenting, classroom management. The stars in the model indicate opportunities for prevention interventions.

This wealth of information has guided the development of prevention interventions that define the intermediate or mediating attitudinal, normative factors that define intentions. It is intentions that have been found to ‘predict’ the initiation of substance use and have become the targets of effective interventions.

Another aspect that is addressed by evidence-based prevention interventions and policies are malleable factors specified in theoretical models of positive and negative behavior change. It is these theories that guide the development of these interventions. Malleable factors are those factors that can be changed, e.g., knowledge, attitudes, skills and intentions around behaviors such as staying substance free. These interventions focus on addressing those factors that can alter or change the behavior of those on a negative life course by promoting positive developmental outcomes and reducing negative behaviors.

Figure 3 presents examples of possible interventions that could be delivered at each intervention point. Currently the best registry available in the United States with evidence-base interventions is Blue Prints (www.blueprintsprograms.org/programs/).

The vulnerability model suggests that in any community at any point in time, multiple evidence-based prevention interventions and policies must be in place to address the needs of the target population. For this reason it is strongly recommended that an implementation system be in place to support and integrate comprehensive prevention programming. Such a system can also sustain these interventions and policies overtime, assuring fidelity and quality of implementation. Evidence-based examples of such systems include Communities That Care (www.communitiesthatcare.net) and PROSPER (http://helpingkidsprosper.org/ ).

Brook, J.S., Brook, D.W., De La Rosa, M., Duque, L.F., Rodriguez, E., Montoya, I.D., & Whiteman, M. (1998). Pathways to marijuana use among adolescents: cultural/ecological, family, peer, and personality influences. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(7), 759-66.

Chen, K., & Kandel, D.B. (1995). The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. American Journal of Public Health, 85(1), 41-47.

Dom, G., Samachowiec, J., Evans-Lacko, S., Wahlbeck, K., Van Hal, G., & McDaid, D. (2016). The impact of the 2008 economic crisis on substance use patterns in the countries of the European Union. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(1), pii.

Hawkins, J.D., Catalano, R.F., & Miller, J.Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 64-105.

Henkel, D. & Zemlin, U. (2016). Social inequality and substance use and problematic gambling among adolescent and young adults: A review of epidemiological survey in Germany. Glantz, M. D. & Pickens, R. W. (1992). Vulnerability to drug abuse: Introduction and overview. In M. D. Glantz, M.D. & Pickens, R. W. (Eds.), Vulnerability to drug abuse (pp. 1-14). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.Sloboda et al., 2012

Henkel, D. (2011). Unemployment and substance use: A review of the literature (1990-2011). Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 4(1), 4-27.

Hill, K.G., Hawkins, J.D., Bailey, J.A., Catalano, R.F., Abbott, R.D., & Shapiro, V. (2010). Person-environment interaction in the prediction of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 110(1-2), 62-69.

Moustgaard, H., Avendano, M., & Martikainen, P. (2018). Parental unemployment and offspring psychotropic medication purchases: A longitudinal fixed-effects analysis of 138,644 adolescents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(9), 1880-1888.

Sloboda, Z. Defining and measuring drug abusing behaviors. (2005). In Sloboda, Z. (Ed). Epidemiology of Drug Abuse. New York: Springer Publications, pp. 3-14

Sloboda, Z., Glantz, M.D., & Tarter, R.E. (2012). Revisiting the concepts of risk and protective factors for understanding the etiology and development of substance use and substance use disorders: Implications for prevention. Substance Use and Misuse, 47, 1-19.